A common stereotype of Buddhism in the West is a monk meditating intensely sporting a shaved head and wearing plain robes. Combining that image with dukkha, one of the religion’s basic tenets that the true nature of all existence is suffering, it may seem illogical for humor to coexist, much less flourish, amid pain and hardship.

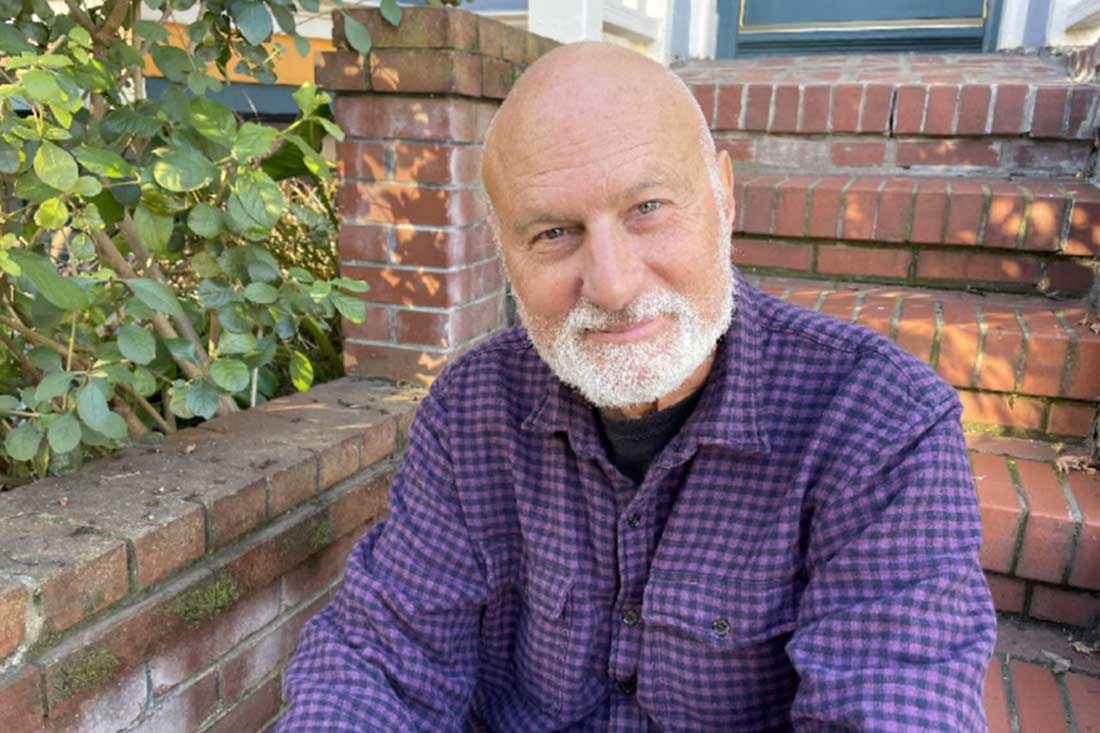

Frederick Marx, an Oscar- and Emmy-nominated filmmaker and author, challenges this notion in his book Turds of Wisdom: Irreverent Real-Life Stories From a Buddhist Rebel. Released in February 2023, the book is a non-chronological collection of essays that Marx says he wrote between the 1980s and 2022. Though the collection has no overarching narrative, it contains loosely linked episodes from Marx’s life and his reflections on varied topics of interest, including his journey as a Buddhist practitioner.

Though Turds of Wisdom is Marx’s third book, it represents his first foray into humor. Along with the play on words, the title reflects Marx’s interest in never letting spiritual practice get too lofty. “I’ve long recognized how the sacred and the profane coexist in close proximity,” Marx says. Unlike his two earlier books—At Death Do Us Part, a memoir of his late wife, and Rites to A Good Life, about how rites of passage can help people live better lives—the tone is self-effacing and more playful.

“Telling people I planned to write this humor book usually launched them into hysterical fits. I was off to a good start,” Marx says.

According to Marx, he got the idea to write the book more than 30 years ago, as he wanted to compile humorous anecdotes from his life. But, he says, he was distracted from it by his first love of filmmaking, earning Oscar and Emmy nominations for his work on Hoop Dreams and Higher Goals. Every now and then, he would write an essay and file it away.

Two of the chapters chronicle his time as a teacher in China. In one about basketball, Marx shares his secret childhood dream of becoming a basketball star, and how he got the chance to show his skills as part of the Tianjin University teachers’ team. Though he says they had to play outdoors, the games attracted spectators. Out of curiosity, Marx asked his teammate and translator how people perceived his play. His colleague summarized the audience response as: “He’s got a nice hook shot, but he doesn’t really amount to much.”

“There went my hoop dreams,” Marx says.

Other essays are a direct look at Marx’s journey with Buddhism, which drew him in as he pondered, and wanted to be free of, his own suffering. He says his first encounter with Dharmic philosophy began in his teens when he read The Book by Alan Watts and Be Here Now by Ram Dass. Both these texts, which Marx insists were foundational in introducing Eastern spiritual practice to Western audiences, influenced him.

Marx says a friend introduced him to Buddhism after a traumatic breakup in 1988, and he decided to fully embrace it. Over the past 35 years, Marx says he has trained with three different schools, beginning with Soka Gakkai International, followed by Vipassana and then Rinzai Zen.

“I was sick and tired of intellectualizing things and just reading books. I wanted to practice something to see if it could make a real difference in my life,” Marx says. “I used myself as a lab rat to find out if I could actually become happier and more enlightened through disciplined action. I still cried every day for a year after losing my girlfriend, but I also had a sense of direction and meaning for my life that I didn’t have previously.”

Born to a Jewish family of German and Russian origin, Marx says he was well-acquainted with the concept of Weltschmerz, or sadness brought about by being aware of suffering in the world.

“My parents taught me at a very early age that people around the world are suffering due to the material conditions of their lives. But what was missing was an acknowledgment of my own suffering,” Marx says. “In other words, I was taught that I can’t suffer because I had it so good compared to others. The Buddha’s first noble truth is typically translated as ‘life is suffering.’ We have to start from the awareness that everybody suffers and that being born into a human body means that we all will suffer to some degree as we experience birth, old age, sickness and death.”

One of the essays in Marx’s book is called “Aging and the Decline of the Human Body.” While Buddhism is never referenced directly, Marx believes the essay’s essence lies in Buddhist thought, as he talks about how people experience decline when they age, when their body is no longer as capable as it used to be. “If you can’t develop a sense of humor about your body breaking down, you’re in for a really rough time,” Marx says.

According to Marx, the aim of Turds of Wisdom is to make public his own suffering, an exercise in finding humor in the universal nature of hardship. By sharing his ordeals, he hopes readers can gain perspective and come to better terms with their own trials, loosening their attachment to their own neuroses.

In the final essay, “Becoming Nobody,” Marx summarizes his life journey. He writes about how, despite his achievements in the arts, he wants to become nobody in the sense of having greater awareness and being more awake—in not taking his own life too seriously. He hopes to leave aside the overwhelming attachment to ego that has him in its unrelenting grip.

“Buddhism has been my North Star for humility. I wrote about how we can balance the ego’s drive to achieve in life and receive recognition for the work that we’ve done but, at the same time, maintain that fundamental humility that, at root, tells us there’s really nothing all that special or unique about any of us. I wrote this book mostly because I recognized the dire state of the world, and I thought if I can do nothing else let me get people to laugh,” Marx says.