Whenever I would see him I used to tell Roger Ebert, only half kiddingly, that as long as he was alive I still had a film career.

He was a tireless promoter of Hoop Dreams. In an effort led by him and Gene Siskel, the Chicago film critics awarded it “Best Film of the Year” in 1994, not best documentary, beating out Forest Gump, Pulp Fiction, and many others. Along with our distribution company Fine Line Features, Ebert and Siskel spearheaded an effort to have AMPAS (the Oscars) nominate it as Best Film of the Year. Then, when the film wasn’t nominated as Best Film or even as Best Documentary, they devoted two of their TV shows and many print columns in their respective newspapers to the outrage. They talked about it on TV shows, in public appearances, at festivals, and in magazines wherever they went.

After Siskel died Ebert continued right on. In a 1999 show with Martin Scorsese, he named it the “Best Film of the Decade.” He took to calling it “the great American documentary.” I believe part of why the film was recently selected by the US Library of Congress as a National Film Landmark, and chosen by members of the International Documentary Association as the “Best Documentary of all Time” was because of the attention he brought it.

Roger truly loved the film. Certainly, he had plenty of good reasons for going out of his way to support it. It was a Chicago product and he was proud of his adopted city. Our production company Kartemquin Films had been producing good documentaries originating there since the mid-1960s. Roger certainly knew them and their work. The film also had the appeal of being an underdog story. We were the little film crew that could, working with a minimal budget, a small “i” independent film, that came out of nowhere to take the country by storm, shot on video no less. Roger liked underdog stories. The film also highlighted the plight of low income, urban African-Americans. Roger was married by that time to an African-American woman who might’ve played no small part in raising his awareness of African-American social issues. But his own social conscience already ran deep. That in itself may have been a decisive factor. Certainly he had many good reasons to go out of his way to support our little film. Not least of which is the fact that he simply believed it to be a great film.

But still I wonder if my long deceased father didn’t also figure in. When I first met Roger in Sept. 1994 over dinner at the Toronto Film Festival I finally got to ask him about stories my Mom had told me for years. “Roger used to toddle along after us following campus film screenings when we went to the campus Union for coffee and discussions,” she’d say.

“Is it true what my Mom used to tell me about you and my Dad?” I asked.

“Who’s your Dad?” he said.

“Werner Marx.”

“You’re the son of Werner Marx?”

“Yes.

“Sit down. I want to tell you a story.”

We sat. Roger proceeded to tell me how my Dad helped him understand how much films could mean, effectively starting him down the road to becoming a film critic. I had no idea. He not only confirmed my mother’s stories, he detailed what an influence my father had been on his career. At that time in the early 1960s my Dad, a spiritual warrior in his own right, was an Assistant Professor of German at the University of Illinois, Urbana. He also co-founded the university’s first film club – the Foreign Cinema Series. Roger was an undergraduate student, attending his hometown school, “following his bliss” (as Joseph Campbell put it) by watching movies.

In many ways I followed in Roger’s footsteps. I too went to my hometown university. I too was profoundly impacted by the Foreign Cinema Club. I too watched as many campus films as I could, eventually graduating with a major in film history, theory, and criticism – not offered in Roger’s day – having taken over 60 hours of film classes in over ten different university departments. I still remember seeing Bergman’s Persona during the summer cinema series when I was only 15. I walked out of Lincoln Hall stunned. I had no clue what I had just witnessed, what the film had actually meant, but I knew I had been deeply and viscerally impacted. To this day I return to that film again and again to absorb more of its profound mystery, beauty and horror.

Though he misremembered my Dad’s first name, Roger wrote about him in his book The Great Movies. On page 253 he talks about the profound cipher that the film Last Year at Marienbad was for him. (I don’t blame him. For me, it’s one of the most inscrutable films ever made.) Apparently, my Dad, in one of their post film, coffee fueled discussions, went on a tear positing the film as an illustration of Claude Levi-Strauss’ theories of anthropological archetypes. Roger comments that he has no idea whether any of that was true; he never read Levi-Strauss. But he goes on to say something lovely and true: The idea, I think, is that life is like this movie. No matter how many theories you apply to it, life presses on indifferently to its own inscrutable ends. The fun is in asking questions. Answers are a form of defeat. That rich observation reminds me of one of my favorite Vaclav Havel quotes: Run toward those asking questions. Run away from those spiritual warriors who say they have the answers.

Like Roger, I also wrote for the Daily Illini. Though I was never editor like he was, I developed my craft at writing film reviews there, which quickly became my first career goal. I can’t say that I wanted to be like Roger. I can say that I was aware how he had built a career out of film criticism and that certainly struck me as a damn good life to have.

Years later, when I saw him at the Conference on World Affairs in Boulder and we spoke on panels together, or when he emailed me with an informal survey he was conducting about the future of film vs. video, I stupidly never picked his brain for further memories of my Dad. He was one of the few living adults I knew who had known him. Most had fallen out of my life, or died themselves, before I came of adult age. Like many sons who lost their fathers too early, I thirsted for reflections of my Dad, never intuiting how much I needed it. He was totally off my conscious radar while deeply inhabiting my unconscious. I deeply regret never asking Roger to open up more fully on the subject of him.

Following our Toronto meeting, I did send him a copy of the short documentary I made in graduate school about my Dad. Maybe I never followed up. Maybe I followed up and Roger never responded. I don’t recall now. But he never mentioned the film, even when we met in later years. It’s entirely possible he didn’t like it. Perhaps he felt uncomfortable in learning about my father’s political past. Maybe it clouded or complicated his own warm memories of Dad. I don’t know. That not knowing is a sadness and a mystery for me.

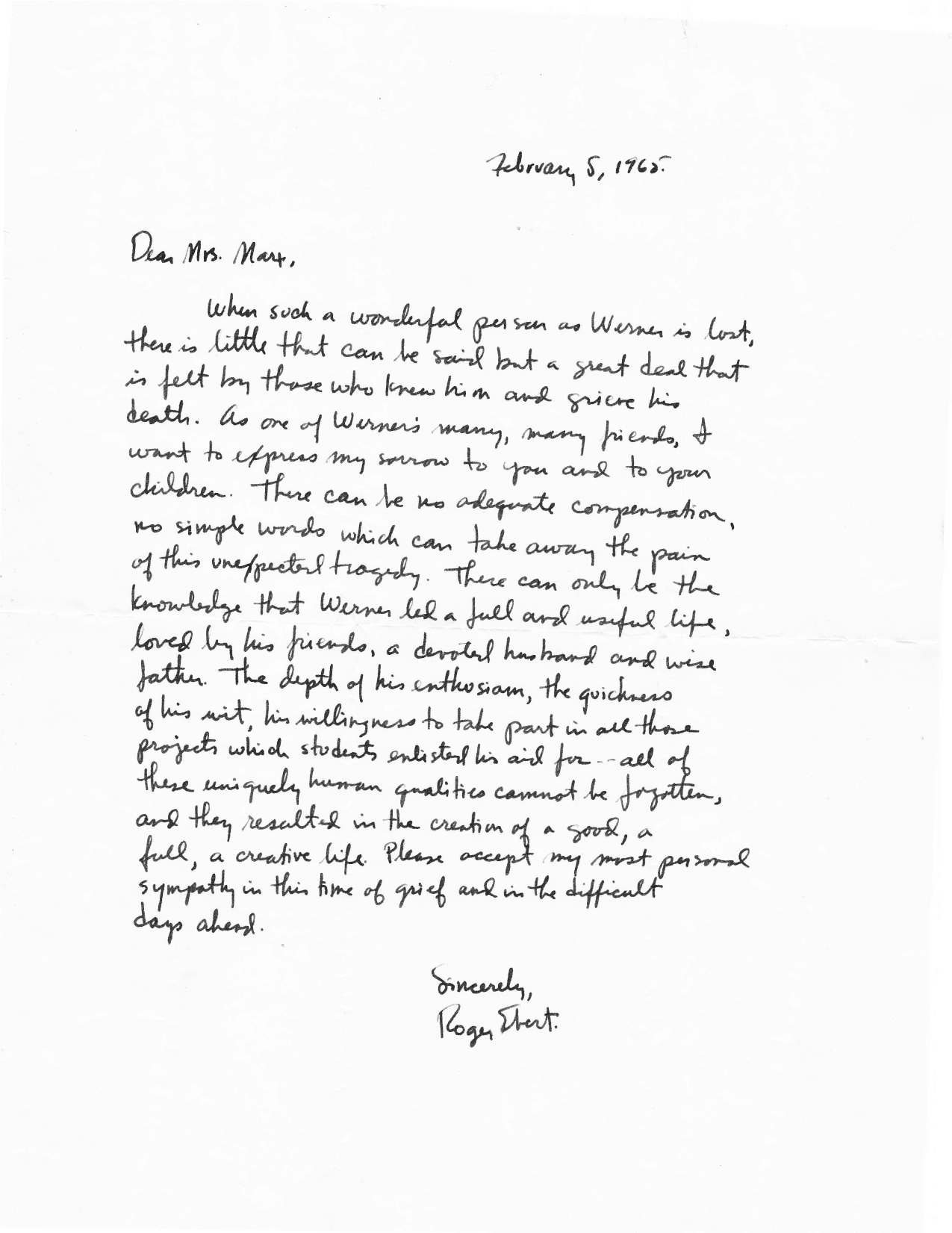

It was a gift of an astonishing sort last March when I discovered two things Roger had written about Dad. I found them while going through my mother’s belongings after she died. Unbeknownst to my brother and sister and me, for almost 50 years she kept a bag full of letters she received following my Dad’s death. In that bag was a tribute article Roger had written in the Daily Illini commemorating him. And among the almost 200 cards and letters was a hand-written letter from Roger to my Mom. Both of these you can read below.

Life is so strange! Odd mysteries, bewildering losses, unexpected gifts… all arrive with surprising fullness. Full of admiration and warmth, Roger wrote movingly about what Dad meant to him. In a perfect reminder of “spot it, you got it” – a maxim of my men’s spiritual warrior work that reminds us that the qualities we admire in others are often those we ourselves carry – Roger celebrates my Dad’s most human values – his love of laughter and ideas, his devotion to teaching and service, his informality, spontaneity, and affectionate camaraderie.

It is another great sadness for me that Roger never got to see my most recent film Journey from Zanskar. I believe he would’ve loved it. Maybe he would’ve championed it. Who knows? Maybe he would’ve shown it at EbertFest – his eponymous film festival held at the Virginia Theater in Champaign where I myself used to watch many a blockbuster as a kid. Maybe he would’ve seized on the story’s strange parallels to Hoop Dreams like another fine writer Pico Iyer did.

I haven’t yet seen Steve James’ film about Roger Life Itself. I’m sure it’s wonderful. For me, Roger’s death is mixed in with my Dad’s and my Mom’s. Maybe the film will help me untie those mixed threads. My fear is that it will somehow make it worse.

Like my Mom, like my Dad, Roger was a fine person who did what he could to show up and make a difference in the world. He had much bigger venues for that than they did. But he shared with them a love of moving images, of how art can shift culture, of appreciating a broad range of different people and ideas, of forming bonds over food and storytelling, of knowing attention paid to one person is as crucial as 100, of accepting humans in all their complexities and contradictions, of never forgetting the forgotten, of living life in its fullness… of life itself. I miss him.

Above Photo of Roger Ebert taken from RogerEbert.com.

what a beautiful post, frederick. thank you.